Nolan Pfister is the heart of Esko’s ‘sisu’ – Duluth News Tribune

[ad_1] ESKO — Senior night is special for any high school athlete, but Thursday’s Esko baseball game vs. Cloquet had particular meaning for Esko senior pitcher Nolan Pfister. Esko’s starting pitcher for the first time, he alternated between walks and singles over the first four batters. A wild pitch allowed a run in. He settled

[ad_1]

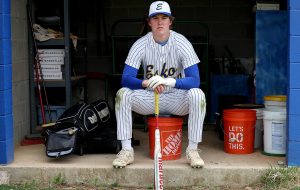

ESKO — Senior night is special for any high school athlete, but Thursday’s Esko baseball game vs. Cloquet had particular meaning for Esko senior pitcher Nolan Pfister.

Esko’s starting pitcher for the first time, he alternated between walks and singles over the first four batters. A wild pitch allowed a run in. He settled down, struck out the final two batters of the inning and went on to allow three hits and two runs in three innings as Esko won 12-2.

Nolan is a contributor for Esko, ranked second in Class AA this season. He has five extra-base hits, seven RBIs and one home run; solid if not spectacular numbers; but consider Nolan had stopped playing baseball for two years before last season.

Even more startling?

The 18-year-old has undergone two open-heart surgeries since 2022. But starting the story there doesn’t provide the entire picture.

Clint Austin / Duluth Media Group

Solid — if not spectacular — numbers, but they become more impressive after learning Nolan had stopped playing baseball for two years before last season. Even more startling is the fact that the senior has undergone two separate open heart surgeries since 2022.

But starting the story in 2022 doesn’t provide the entire picture.

On Oct. 11, 2019, Nolan, then 12, was at home on a Friday night with his dad, Matt Pfister. His mother, Brooke Pfister, was watching his older brother, Jackson, play with the Esko football team in Aitkin. Earlier in the day Nolan learned he had earned a spot on his Pee Wee A hockey team.

“I was fired up that day because I worked hard and I made that team,” he said. “I was just watching TV, (Matt) gets a call from my mom and things emotionally kind of escalated and I was like, ‘What’s going on?’”

Matt got off the phone in tears, Nolan said. Soon after, Nolan was packing, then in the car with his grandparents to stay at his cousins’ house for the night.

During Esko’s game at Aitkin, Jackson suffered a cardiac emergency on the field. By the time Matt reached the hospital, his oldest son had died.

After Jackson’s birth in 2003, he was diagnosed with a congenital heart defect and treated at Children’s Hospital in Minneapolis. About six months before the season began, though, Jackson got a “clean bill of health,” according to Matt.

“It wasn’t until after his death that we recognized that he had an underlying heart condition — aside from the one he was born with,” Matt said.

When Nolan was a toddler, he was tested for the same condition as his brother, but it indicated he didn’t have similar problems. The only reason they learned about Jackson’s underlying condition was a result of a DNA test after his death.

Matt said he and Brooke were “going back and forth” about whether to test Nolan, but a “pivotal moment” for the family came during a football practice during Nolan’s freshman year.

“He was playing fullback and he had like a 25-yard run,” Matt said. “I was like, ‘He seems gassed, but he seems a lot more gassed than he should be.’ It was the moment where I realized we have to get him checked out again.”

The Pfisters reached out to the Mayo Clinic for more testing and by May 2022, they learned Nolan had “congenital heart disease” as well as a “genetic defect,” according to Dr. Michael Ackerman, a genetic and sports cardiologist at Mayo.

Clint Austin / Duluth Media Group

“One of his four major valves in his heart wasn’t designed correctly and he has what we would call severe tricuspid valve dysplasia,” he said. “It wasn’t working right, either — it was leaking severely.”

Jed Carlson / Duluth Media Group

Nolan was scheduled for surgery in July 2022 to attempt a repair of the valve and add an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) to his heart.

An ICD is a small, battery-powered device designed to detect and stop irregular heartbeats or arrhythmia and, when needed, it delivers an electric shot to restore a regular heartbeat, according to the Mayo Clinc website.

Until the ICD could be implanted in Nolan’s chest, he would need a “LifeVest,” a wearable defibrillator. While his parents were fans of the safety, there was one person who was less than thrilled: Nolan.

The water activities that punctuate any Northland kid’s summer were impossible, but basketball, running, jumping — anything that causes someone to sweat — was out of the question for Nolan with the vest. He could lift weights, but even that turned out to be a problem.

“He hated that thing so much,” Matt said. “There were times he would take it off when he was in the gym lifting and preparing for football. He’d take it off and we would get a phone call saying there’s a problem. That would scare the s— out of me and mom.”

‘The most pain I’ve ever been through’

Once July arrived it was time for surgery, but this is no simple operation like most injured high school athletes undergo. Nolan’s doctors had to split his sternum to access his heart.

It wasn’t just physical pain — though there was plenty of that, according to Nolan. The process was mentally painful and affected every aspect of his life. A side sleeper, Nolan had to sleep on his back for the first time and needed help just to get out of bed.

Photo submitted by Brooke Pfister

“I couldn’t sleep at all in the hospital and my back was really sore and in pain,” he said. “I couldn’t get myself up to go to the bathroom and for a few days I was throwing up medication because I could barely eat anything. I was just in pain, 24/7. It was the most pain I’ve ever been through physically.”

As the initial pain of the operation began to recede, Nolan’s thoughts returned to football and getting back on the field. It was “crushing,” he said, to miss the 2022 season but in October, Nolan was cleared to start lifting weights and begin trying to get back into football shape. Nolan dedicated himself to the weight room. He skipped a second consecutive baseball season, but the work paid off in the form of 50 additional pounds of muscle. As the 2023 season approached, Nolan seemed to be on the cusp of a big return to the field for a team expected to be among the best ever assembled in northern Minnesota. Esko was ranked in the top five all season in Class AAA football, led by Koi Perich, now a star with the Minnesota Golden Gophers.

Nolan’s ICD went off in practice the week before the season started, but it seemed more like a bump in the road. After a conversation with Ackerman at the Mayo Clinic and a discussion with then-Esko coach Scott Arntson, the decision was made to limit Nolan to play just defensive series in the season opener at Duluth East. They also agreed that Matt would be on the sideline for Esko games that season. Matt told Nolan to tap the top of his helmet if he felt at all strange.

Esko took the opening kick back for a score and the defense — and Noland — took the field.

He saw a Greyhounds running back coming toward him and he lowered his head — probably a little too low, Nolan said — and he “got popped in the head really hard.”

“All of a sudden I start to get dizzy,” he said. “I’m like ‘Whoa, what the heck’ and I’m looking at the ground and panicking a little bit. Then I remembered him saying, “Just tap your helmet if you feel anything weird and I did that.”

Nolan thought he crouched down and put his hands on his knees.

That’s not what happened.

“He taps his helmet and I’m like oh s—,” Matt said. “He immediately starts running…Before he can get to the sideline, all of a sudden he just drops, face first.”

Matt and Esko trainer Tom Nooyen raced toward Nolan on the field and it was Nooyen who Nolan saw first when he regained consciousness.

Jed Carlson / File / Duluth Media Group

“He’s like ‘Noles, keep looking in my eyes,’” Nolan said. “I was confused, I had no idea what happened and he’s like, ‘You got zapped again.’”

After being checked out at Essentia Health after the second incident, the Pfisters decided they were going to take Nolan back to Mayo for some further testing.

The incident cost Nolan his first week of school and it wasn’t long before it was determined he would need another open-heart surgery. There were questions, sadness and anger.

“… To learn that I worked that hard for it all to just be f—ed in that instant — there were a lot of tears. It was not a good time in my life,” Nolan said.

Nolan’s cardiology team knew the first surgery to repair the valve might not be successful, but a repair was a much better solution for Nolan than a valve replacement, which would require him to take blood-thinning medication that would preclude him from ever playing a contact sport.

‘I did it once, I can do it again’

The news that he would need more surgery didn’t just send Nolan reeling. After all that work to get himself back on the field, he was out there for one play. Even his friends had questions.

“It was really like, is he even going to get back to playing sports, being as big and fit as he was before,” teammate and cousin Sam Panger said. “After the first surgery we all thought it was just a bump in the road and he’s going to get back on track. But after the second, it was an even bigger step back and we were wondering how he would ever recover from it.”

Jed Carlson / Duluth Media Group

Nolan’s surgery was scheduled for January 2024. Even before the first surgery he had gone to play catch with some of his friends on the baseball team, then open gyms and batting cage sessions, but time came for the operation, which was more difficult than the first.

“It was a lot more painful and mentally challenging than the first one,” Nolan said. “I remember I worked so hard to gain all the muscle back and now I’m losing it again. I thought, am I going to work as hard to do this again? I just kept telling myself, ‘I did it once, I can do it again.’”

Nolan determined that he would return for the 2024 baseball season — something that, in hindsight, was probably a mistake.

Esko was the reigning Class AA champion in 2024 and a top-five ranked team all season, but Nolan only appeared in five varsity games. It was a season filled with strikeouts, miscues and failures. He didn’t handle it well.

“I was getting down on myself mentally and I forgot the whole point of baseball,” he said. “It’s such a game of adjustments and the mental challenge is that you have to move on to do better. It will eat you alive if you don’t.”

‘The best decision for me’

Before his second surgery, Nolan made the decision to “medically retire” from football. Ackerman and his doctors at Mayo believed he still could play, but Nolan felt he would always be limited on the field.

Still, football was his “passion” and an itch he needed to scratch. He was having a hard time watching his senior football season pass by, but Arntson asked him to coach Esko’s middle school team.

“I was hesitant at first, but I said year and it really was the best decision for me,” Nolan said.

Middle school football isn’t the highest end of coaching, but it helped Nolan think about his condition a little differently.

“My dad has really helped me learn a lot of this stuff,” he said. “He’s told me many times: what’s the point of worrying about things you can’t control. I can’t control this heart condition — I was born with it, it’s never going away…I’ve done a lot better since then.”

As the fall wore on, Nolan started regaining muscle and weight that surgery had caused him to lose, again.

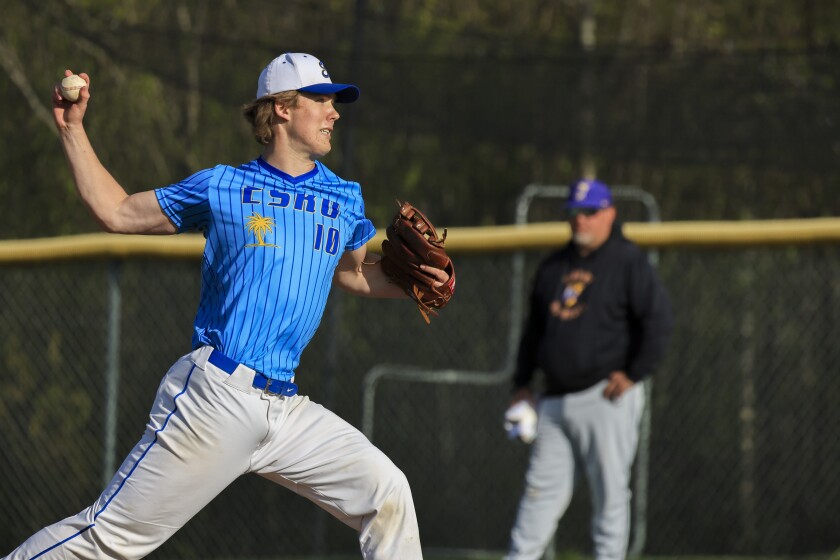

On the baseball diamond, Nolan found himself not just a starting outfielder on a team that lost a ton of experience from last season, but a team contending for a second state title in three years.

“To be able to be in the mix in the top 10, 11 guys on this team just speaks to the kind of athlete that he is,” Esko coach Ben Haugen said. “Even though he is raw, he lacks some experience, he’s still able to go out and compete on a really good team.”

Perhaps his most memorable moment was against Mesabi East on April 21 when he hit his first varsity home run.

“It was a full count and I just crushed it to right field,” Nolan said. “The moment was so surreal — I was like ‘I just hit a home run.’”

Clint Austin / Duluth Media Group

Perhaps the only thing that wasn’t perfect about the moment? His parents were still driving to the game in Aurora. Matt was able to see video of the hit in the car, but even when his friends started giving him a hard time it didn’t matter.

“I didn’t have to see it because I knew what he felt when he hit that home run,” Matt said. “I felt so good for him. It was like he finally made it — you know — he made it.”

Baseball is a game of failure — the best hitters in the world fail more often than not — and learning from those setbacks. Even Nolan’s first inning on the mound Thursday wasn’t unfamiliar, Haugen said, when the first four batters reached base.

“It always seems like bad things happen to him and then he just figures out a way to persevere and get through it,” he said. “He wants to come back for football and it doesn’t work out. He missed some baseball seasons with various things, but he just keeps plugging away and gets through it.”

Clint Austin / Duluth Media Group

Through the tragedy, through the setbacks, Nolan has worked to heal and continue competing, whatever that form that takes. Baseball is a sport of timing and repetition, missing whole seasons and coming back at all — minus serious heart conditions — is extremely difficult.

“Sisu” is a Finnish term with no literal translation, but it describes determination or resilience in times of difficulty. It’s always been a part of the traditions and community in Esko, but in the wake of Jackson’s tragedy, sisu became a rallying cry.

Nolan’s sisu has become an inspiration for the community, but the community — always proud of its Finnish roots — embraced the Pfisters with the same sort of vigor.

Clint Austin / Duluth Media Group

“That strength and resilience in the face of adversity defines who we are as a community,” Brooke said. “We rally and cheer Nolan and his teammates on because they embody our sisu tradition. It’s Esko pride, it’s the cornerstone of our culture. I am forever grateful that Nolan shows that light — which comes from his brother. We couldn’t have gotten through this without all of that support.”

Down the line Nolan could need a heart transplant, according to Ackerman, but it’s been nearly two years since the last time the ICD shocked his heart.

“His heart is behaving, it’s not worsening and he is thriving,” Ackerman said.

For Nolan, he’s just glad he’s able to get out and play something — anything — with his friends.

“Every day, I thank God that I woke up today,” he said. “After all that I’ve been through, if I could go back, I wouldn’t change it. I’m just thankful I get to wake up and play baseball.”

[ad_2]

لینک منبع

برچسب ها :

ناموجود- نظرات ارسال شده توسط شما، پس از تایید توسط مدیران سایت منتشر خواهد شد.

- نظراتی که حاوی تهمت یا افترا باشد منتشر نخواهد شد.

- نظراتی که به غیر از زبان فارسی یا غیر مرتبط با خبر باشد منتشر نخواهد شد.

ارسال نظر شما

مجموع نظرات : 0 در انتظار بررسی : 0 انتشار یافته : ۰